Emerald Lotus

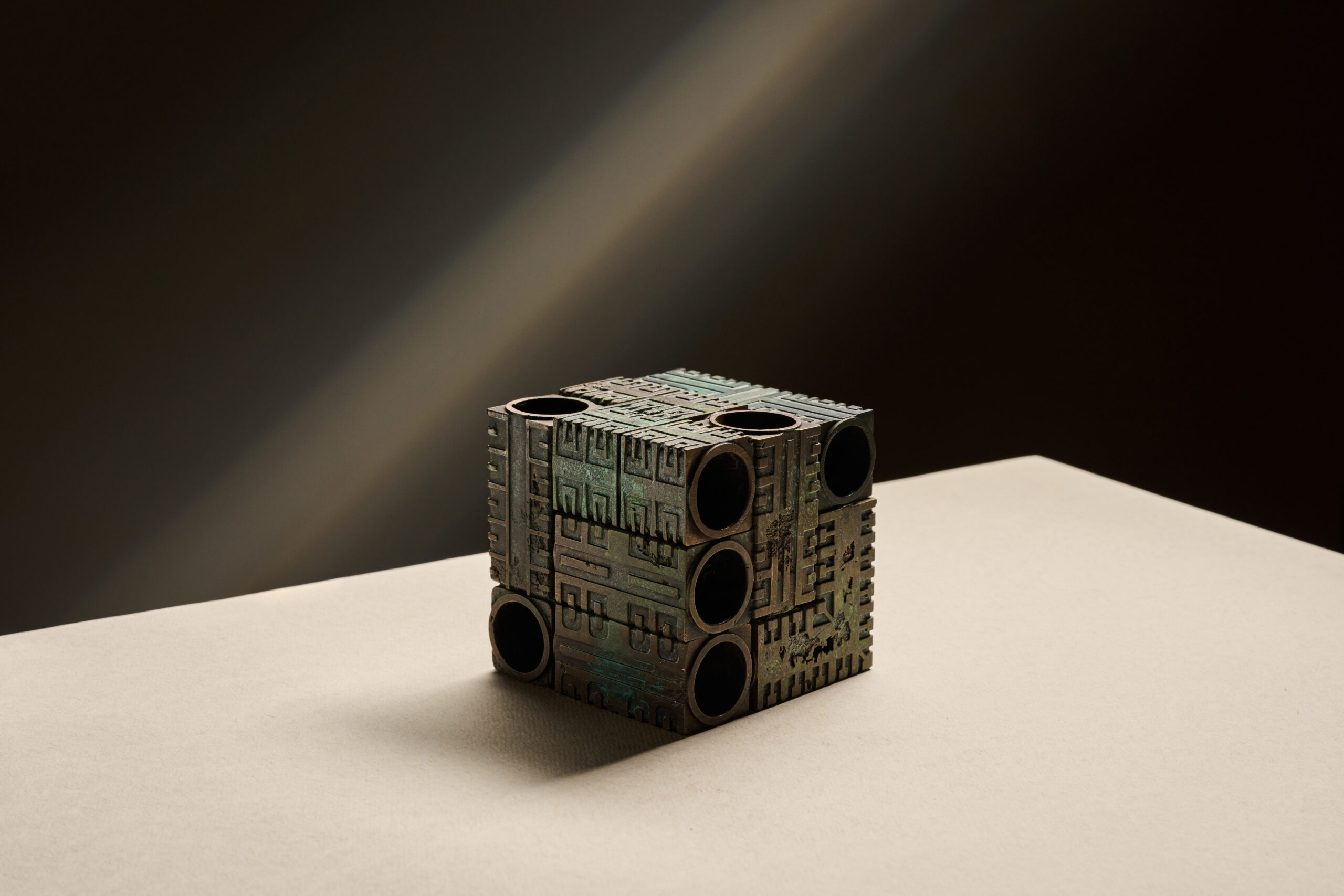

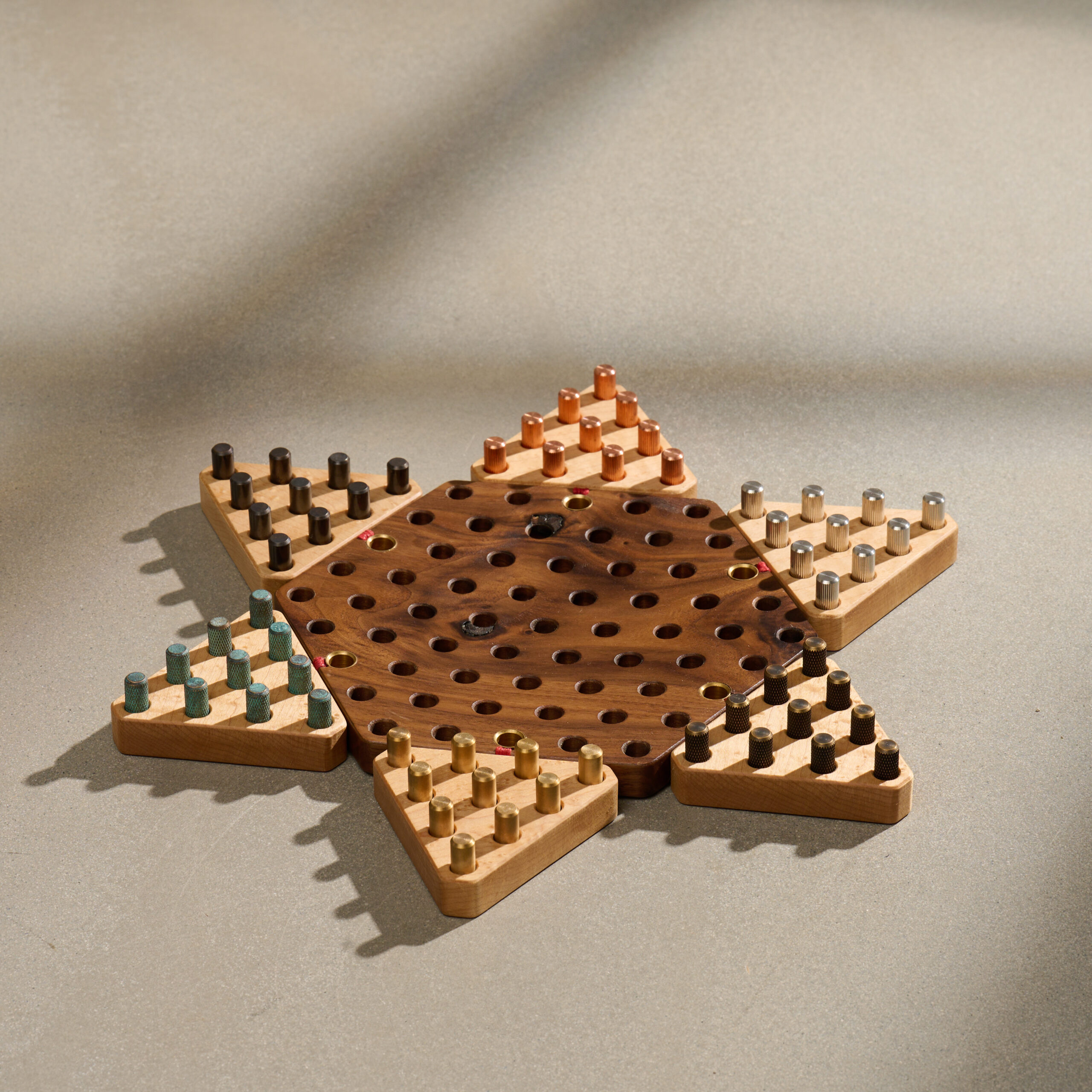

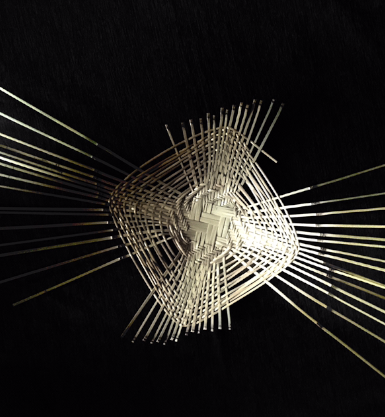

Following his exchange with tradition craftsmen the Luk brothers from Ping Kee Copperware, Anthony So employed the traditional metal forging technique combined with the craft of enamelling, and produced a hexagonal tea tray to match with Ping Kee’s tea sets. The hexagon is an unconventional shape for copperware, which normally follows a round shape, but its natural geometric form allows a flat conherant surface to be formed when several hexagons are put together. The tea tray together with the hexagonal enamelled small plates belong to the same series of works. During the fabrication of the tea tray, the surface was deliberately creased to create a natural and rough surface which reflects the handmade quality. The forged metal containers are then coated with layers of enamel under high temperature, while silver leaves are used to create patterns and imageries that embody the Oriental aesthetics. The filter of the tea tray is a stencil made of brass, and is carved out using the traditional Chinese paper-cutting method, creating a lotus flower-patterned filter which is both aesthetically pleasing and practical. The hexagonal enamelled copper tea tray is accompanied by a tripod, and the combination reinvents the traditional design of the three-legged vessel by adding a contemporary touch.

Story of the Traditional Craft

In the 50s and 60s, there were around 30 copperware stores in Hong Kong. However, sharing the same fate as Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry, in the 80s, the copper forging industry started to decline, and nowadays, the only remaining business is Ping Kee Copperware.

Luk Shu-choi and Luk Keung-choi started learning copper forging at a young age from their father Luk Ping, which was the common way of how traditional craft is perpetuated by passing on from one generation to the next.

The two Luk brothers would sit on a small stool every day, regardless of the weather condition, hammering copper and creating different kinds of objects by hand, from a small spoon to the huge boiling vessel seen at the Chinese herbal tea shops.

The encounter between Ping Kee Copperware and their customers often involves a personal story with the objects. There is a loyal customer who has developed an intimate bond with the small copper pot from Ping Kee, and she has been using the pot for cooking Cantonese congee for years. As the customer aged and moved to Singapore, every time her daughter visited her relatives in Hong Kong, she would ask her to purchase a small copper pot from Ping Kee back home, as only the Ping Kee’s copper pot could bring out the true flavor of the congee. Besides recurrent local customers, the craftsmanship of Ping Kee is also being appreciated by young Japanese who are passionate about the craft culture. Customers would customize a set of copper coffee cups to go with their minimal and wabi-sabi style coffee shop, which is also a way to pay homage to the handicraft.

Back in the days, the best-selling item from Ping Kee was the brass teapot. The relationship between brass teapot and Hong Kong culture has to be traced back to the Cantonese style yum cha culture.

In the past, the old-style traditional Hong Kong tea houses would mostly serve tea with dim sum, which was the most symbolic of Hong Kong’s yum cha culture. The tea would be served in a cup with cover, and the waiter would add water to the tea using a brass teapot. In the 50s and 60s, waiters who served tea were known as “Tea Professors”, and they would be holding a huge brass teapot, aiming at the tea cup, and pour water into it three times without spilling any water out of the cup. This is a traditional etiquette in tea ceremony, which is also a way to show respect to the customers and the tea itself. However, as there is a risk of scalding customers when serving tea in a hot water-filled brass teapot, in recent years, stainless steel teapots have been used instead, and sometimes the teapots are brought to the electric boilers to be refilled before being returned to the table. The profession of “Tea Professor” has also been dying out, and the traditional way of serving tea would only be used in long-established local tea houses.

|

|

Making Process

The copperware at Ping Kee is generally forged using copper or brass. Copper, in its purest form, has a light-red luster, and due to its malleability and high melting point, as well as a high viscosity, it is not suitable for casting big containers, and is instead combined with other chemical elements to form alloys. Brass, for instance, is an alloy of copper and zinc, with a golden appearance as well as the luster and properties of metal.

Traditional copper forging is generally performed by hammering a metal sheet placed on an anvil in concentric movements, causing the metal to compress or extend while avoiding the formation of creases. The pots and cups from Ping Kee Copperware are forged using this principle and technique. The production of copperware requires a large sheet of copper to begin with, which is akin to tailoring clothing using fabric. To fabricate a large copper teapot takes around twenty days. The whole teapot is made by hand, and both the Luk brothers think that the sprout is the most challenging part to manage, as the form is difficult to shape, and has to be precise so that it could be connected seamlessly with the body.

Artworks from same series

OTHER WORKS FROM EXHIBITION

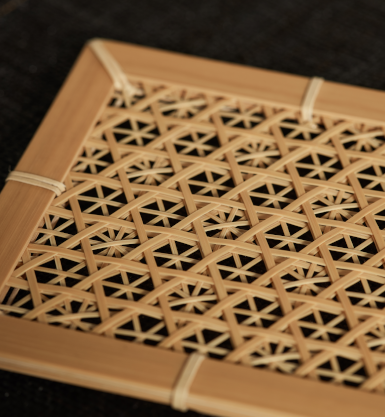

Auspicious Horizons

Yue Kee Rattan Factory & Ahung Masikadd & Barnard Chan & Cecilia Lai